~ Delta Poetry Review ~

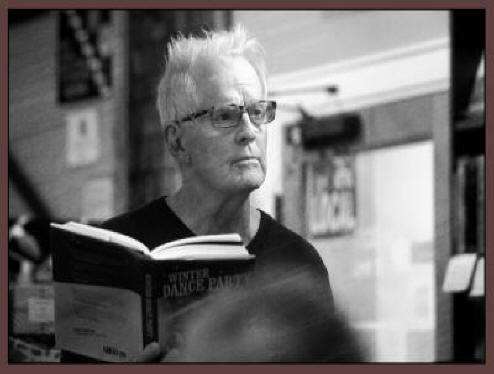

David Kirby, Featured Poet

David Kirby

teaches at Florida State University. His latest books are

The Winter Dance Party,

Poems 1983-2023,

and a textbook modestly entitled The

Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them.

Kirby is the author of Little Richard:

The Birth of Rock ’n’ Roll, which the

Times Literary Supplement described as “a hymn of praise to the

emancipatory power of nonsense” and which was named one of

Booklist’s Top 10 Black History Non-Fiction Books for that year.

Entertainment Weekly has called Kirby’s poetry one of “5 Reasons to

Live.” Kirby has also received a Lifetime Achievement Award from

Florida Humanities, which called him “a literary treasure of our

state.”

Sramps

I learned everything I know about life

growing up in the wilds of Louisiana,

the most important being that there is

no wrong way to say or spell the word

“shrimp.” Sramps, scrimps, shrimpses:

no matter how you said it, the nice man

at the seafood store or the sweet lady

at the food truck would hand you your

pound of stalk-eyed arthropods in a plastic

sack with enough ice to keep them fresh

on the drive home or else your little

cardboard box containing a dozen lightly

breaded and flash-fried pinks with fries

and slaw, tartar or cocktail sauce. Or both.

SRAMPS! proclaims the hand-lettered

leaning against the cooler at the corner

of Scenic and Essen Lane, its owner dozing

in the late-afternoon sun and rising

unsteadily when he hears your tires

crunch the gravel to blink, then smile

as he hands you as many bags of sramps

as your seafood-loving heart desires.

Did not Derek Walcott say in his Nobel

Prize acceptance speech that the fate

of poetry is to fall in love with the world?

Words like “sramps” help with that.

No mistakes out there, just opportunities.

Mary’s Song

Ever wonder why we like stuff? Art, music,

poetry?

It’s easy to say why we don’t like it: too long, too short,

too loud, too soft, too obvious, too weird. Of

those,

I think “too obvious” is the worst charge you can level

against a painting or pop song or romance novel,

don’t you?

We readers know that in

reading, as in life, even if you

think you know where you’re headed, you really

don’t, and the same is true for artists of every kind: Kant said

Newton knew what he was doing and could take you back

through the steps logically, whereas Homer had no idea

and couldn’t possibly explain it either. Ha, ha!

You got that right, Immanuel! I was in McDonald’s

the other day and heard a guy tell his friend that

his favorite books were “thrillers with a little

bit

of truth,” and when I heard that, I thought,

boy, I really need to read those books, not to be thrilled

but to get just a little bit of truth, since I’m sure

I’d be unable to handle more, and then I thought,

nah, you can do better than that, buddy. You

need

to buy in. You need to invest. What, you think

Jackson Pollock splashed out “Number 1 (Lavender

Mist)” while he was waiting for his coffee to

cool,

that Beethoven knocked out his Ninth

Symphony on his lunch break, Homer wrote The Iliad

one afternoon while he was floating around

the Aegean on an air mattress? These things

take time, you know. When Jesus is born,

angels appear in the sky and start singing

hosannas at top volume and shepherds run over

to see what’s was going on and then rush off

to tell everyone else what’s going on

and the ass is braying and the cow is lowing and the dog

is barking and in the midst of this

hullballoo,

“Mary treasured up all these things,”

according to Luke 2:19, “and pondered them

in her heart.”

You have to treasure up, sure—

you’ll never get anywhere as an artist if you don’t

treasure up—but the pondering part is what

counts.

Things are everywhere. Things are a dime

a dozen these days. We all have the same things: bills,

backaches, beer cans,

boyfriends, bee hives (the structure

in which bees sleep), and bee hives (the domed

and lacquered hairdo made popular in the sixties

but still fashionable in some venues, thank god),

and that’s just the second letter of the alphabet

and not even all of it. And what came of Mary’s

pondering? Well may you ask. Possible

answers include nothing, a lot, everything, all of the above,

none of the above. I pick answer E. When Caliban

tells Stephano and Trinculo that Prospero’s isle

is filled with sweet airs that make him sleep

and dream, he hears a thousand twangling instruments

humming about his ears and then wakes to such

beauty as makes him cry to sleep and dream

again,

and that’s what we want. We want to cry—

or jump! Kingsley Amis said he only wanted to read novels

that began, “A shot rang out.” We don’t like surprise

in life-life but love them in our arty life, or at least

A. E. Stallings does. A. E. Stallings says that

she lived in Athens (our Athens, not theirs) when

R.E.M. became

so famous that they couldn’t appear

anywhere without being overwhelmed, so they

started

playing under fake names like Beast Penis,

though sometimes you’d go to a Beast Penis concert only

to find out it really was Beast Penis and they were good—

not R.E.M.-good, but you’d discovered a new band

and had a great night out with your buddies.

Of course I haven’t yet mentioned the responsibility

that art has to us, so let’s take care of that right now.

Art, you have to hold up your end of the

bargain.

Be bold, art! Paintings, be splashier!

Be big—miniatures are for chumps! Novels, thrill us

and tell us the truth, too, but tell it slant.

And when you fail, fail big: four or five years ago,

we’d stopped at this wine bar in Florence for a

snack

before going to an experimental performance

at the Teatro Goldoni, and when I told our server,

she said, “Experimental work is either bene-bene

o male-male,” that is, very good or very bad,

and today when we were at that wine bar again and I was

paying our check at the counter, I reminded her

she’d said that, and she asked me “So which was it?”

and when I said, “Male-male,” all the

guys

behind the counter burst into laughter.

Not a problem for Jesus’s mom, I’m so sure,

though we’ll never know, will we? Yeah,

she treasured up and pondered what

she heard and saw, but then what? There’s no record

of any reflections on or memories of Our Savior’s birth

on her part, not in Matthew or Mark or Luke or John

or any of the Gnostic gospels: zip, null, nil,

nada,

rien, niente, Nichts, zilch, bupkis,

balderdash.

Let’s face it, we’ll never hear Mary’s song.

Goddamn it. Goddamn every goddamned

thing in the world to hell anyways!

Oh, wait, I know—we just have to write it ourselves.

I'm Here to Help You

Friend I hadn’t seen in a long time said, “I’m still writing

poems, but I no longer use letters and words,

instead I just invite my audience to breathe with me

and create their own meanings and

interpretations,”

and then, “Just kidding.” Man’s got a point, though:

did you know that just 7% of a speaker’s message

is expressed through words? That’s a sure-God fact,

according to a 1971 UCLA study that says 7%

of meaning is communicated through the spoken word,

38% through tone, and 55% through body language.

Now if you were illiterate and had no gardening skills

and lived in the midst of the political and

cultural

disarray that plagued Western Europe during

the early Middle Ages after the fall

of the Roman Empire, I’d recommend that you move

next door to a Benedictine monastery, seeing as

how

those holy fathers served as a bright-as-day resource

during that dark period by introducing

their neighbors to cutting-edge farming methods

and also, when a majority of the continent was

unschooled,

promoting literacy and preserving classic manuscripts,

thus laying the foundation for European

universities

as well as that flowering of the arts and sciences

we know today as the Renaissance. But as you are

the proud possessor of a couple of healthy houseplants

as well at least one overpriced college degree,

I’m sure you’re more than capable of figuring out

how to get things done on your own. If you’re

lucky,

you’ll be like the George Eastman who developed

a little handheld camera he called the Kodak

because the name was easy to remember, difficult

to misspell, and meant nothing, meaning it could

only

be associated with itself. If you’re unlucky, you may

end up like Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce,

Baron de Clootz, a revolutionary French nobleman

better known as Anacharsis Clootz who devoted

his fortune to the advancement of humanitarian ideals,

at one point bringing to the National Assembly

a delegation of thirty-six foreigners which included

Russians, Poles, Germans, Swedes, and Italians

but also but also Muslims from the Middle East

and North Africa. Anacharsis Clootz was sincere

but eccentric—in the end, too eccentric

for Monsieur Robespierre and the other members

of the Committee of Public Safety who saw to it that his head

was struck from his shoulders on 24 March 1794.

They were just jealous they hadn’t come up with that idea

themselves, don’t you think? Anyway, somewhere

on the scale

between George Eastman, who thought big but not

too big, and Anacharsis Cloots, who was, like,

way out there, you are likely to find such figures

as David (no relation), the guy who does body

work

at the car shop down the street, and who, when I asked

how he succeeded at his job, at which I might

say

no one is better, thought for a minute and then

said, “Artistry, chemistry, and ignorant

perseverance.”

Now your garden-variety nitwit or pinhead would have said,

“Ignorant perseverance—see? You don’t have to be

smart,

just work hard.” Yet David not only valorized, emphasized,

underscored, and foregrounded the other two

elements

in his formula yet also put ignorant perseverance last: artistry

and chemistry are essential, sure, but that

third quality

is the lineman who pushes the fullback into the end zone,

the cue that sinks the eight ball in the corner

pocket.

Or, as Jimi Hendrix said, “Learn everything, forget it,

play.” That said, the unhappy fact remains that,

try as you may, your best-laid plans and most rumbustious

exertions might get you exactly nowhere, which

might

or might not have something to do with your horticultural

skills or inventiveness or pool-hall know-how

or lack thereof and might instead be determined

by circumstances entirely beyond your control.

Everybody’s drawing can’t go on the refrigerator.

Since everyone’s drawing can’t go on

the refrigerator, that means the most efficent way

to get through hard times is to heed

the wise counsel of pioneering Southern bluesman Gregg Allman,

who saw his brother and fellow band member Duane

as well as bassist Berry Oakley die in separate motorcycle

accidents even as other band members indulged

in the heroin habit that Gregg himself succumbed to

just as the group was reaching its peak,

yet somehow was able to say later, “Success is being

able to keep your brain inside your head.”

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by their failure

to do just that, so thank you, Gregg Allman!

Thank you for this excellent suggestion as well as for

“Little Martha” and “In Memory of Elizabeth

Reed.”

Stay

You tell me you know a woman who lost her aunt

to suicide and finds no peace: she can’t sleep,

you say,

and when she’s awake, she cries all the time. A friend

says she can guide her back to a former life

that

is still taking place in a kind of in-between world,

one like heaven, a world in which she might find

lost loved ones, including that aunt, and when

the woman says she doesn’t believe in that kind

of thing, the friend says you don’t have to

believe,

just try it, and she does, and as she is going under

she wonders if she’ll hear a great voice out of heaven,

as the Book of Revelation says, and there shall

be

no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither

shall there be any more pain, but no, it’s not

like that

at all, it’s just her in a new body, in a country

she’s never seen before, speaking a new language,

and look, there’s her aunt, and they hug each

other

and she says, Aunt Mary, why did you do it?

People still laugh at the jokes you told. They

remember

what you said, how you helped them, told them

they were pretty, they were smart, that you loved them.

Why did you leave us? Why didn’t you stay?

And her aunt shakes her head and looks down and then

up at the woman again and says, Nobody told me

to.

You tell me that a stay of whalebone or wood was part

of a support garment that lifted the bust

in the 18th century, trimmed the waist,

held you erect: “Stay!” it cried to your bosom and belly,

to the shoulders that slumped from bending over

a pianoforte or your sewing or that novel

you were reading by the light of a single candle.

“Stay”

is also a doo-wop song recorded in 1960

by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs and many times

thereafter by other musicians and for good

reason,

since “Don’t go—stay!” is what we say

when our sweetheart is standing in the door

and looking back at us for the last time

or our brother is dying or we’re petting

our good boy or girl and he or she is wagging

his or her tail as the vet readies his syringe

and we say “please, not yet” and then

“don’t go, please stay, just a little bit

longer.”

In a single tragic instant, a pianist loses

his eight-year-old daughter, the one he took

with him

to every practice, who sat next to him on the bench

and turned the pages for him, face furrowed with

attention and then smiling as he plays the final

chord.

For the next two years, he has just one wish:

let me keep her, he says, I just want to keep

her,

and then one day he’s passing by a rehearsal room

and hears someone practicing an aria and remembers

that Verdi was writing a comic opera called

Un Giorno di Regno even though his first two children

had died and their mother, whom he loved dearly,

also died just after at the age of 26, yet the impresario

who commissioned the work refused to release

Verdi from his contract, so it should come as no

surprise

that Un Giorno was a failure and closed after

a single performance. After that, it was tragedy

after tragedy—Aida, La Traviata, Rigoletto—until,

following the success of Otello in 1887,

80-year-old Giuseppe Verdi decides his last

opera

will be Falstaff, a comedy, saying, “After having

relentlessly

massacred so many heroes and heroines,

I have at last the right to laugh a little,” and I knew

I wouldn’t laugh, said the pianist, at least not

for a while, but I had to work, he said, and he

did,

he just kept working, there was nothing else to do.

And then the pianist adds an afterthought.

He has never forgotten his daughter, he says,

not for a second, and when he performs now,

she is with him as she was then. The lights

in the concert hall are down, and a hush

falls over the audience as the conductor takes

the podium, then turns and nods to cue his entrance.

As he waits in the wings, the pianist says, there she is.

Only he can see her as he steps onto the stage.

Kafka says that “life’s splendor forever lies in wait

about each one of us in all its fullness

but veiled from view, deep down, invisible, far off.

It is there, though, not hostile, not reluctant,

not deaf. If you summon it by the right word,

by its right name, it will come.” Is “stay” that word?

Is that it? I say. Yes! you tell me. Yes, it is.

But each of us must say it in our own way.

Happy Chemicals

did you know

you’re just a bunch of chemicals

with an electric charge

though you shouldn’t feel bad about that

so am I so is everyone

I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings

come on kiss me & let’s make up

chemicals are in balance in nature

it’s when we start combining them in new ways

that we create chaos

also ecstasy as atoms collide with

or repel one another

& electrons zip around the atoms

in a rush to bring the separate elements

together

when I ask my friend

the chemist how many experiments fail

he doesn’t hesitate

80% he says

and points out as well that chemists like to

tell each other

I’ve just come up with something that will

either save humanity

or annihilate it

though neither ever happens

which is why they keep going back to the lab &

trying again

the way lovers do

as they pursue & bond & break up with each other

until they find the one person

they can’t live without

the way musicians do

when they try to write songs

most attempts at song writing are failures as

well

though the ones that work really work

because they release

that’s right chemicals in their listeners’

brains

happy chemicals such as dopamine & oxytocin &

serotonin

which is why the brain scan of a person

who is staring at a blank wall looks like a

satellite image

of North Korea at night

whereas a brain scan of that same person

listening to a Bach cello suite

looks like Times Square on New Year’s Eve

no wonder

the memory of a great concert can stay with you

for years

also a great kiss

why yes I do believe I would like one

and another and another after that and another

and one more

| Archive | Submissions | About | News |