~ Delta Poetry Review ~

Denton Loving's Book Review by

Stephen Furlong

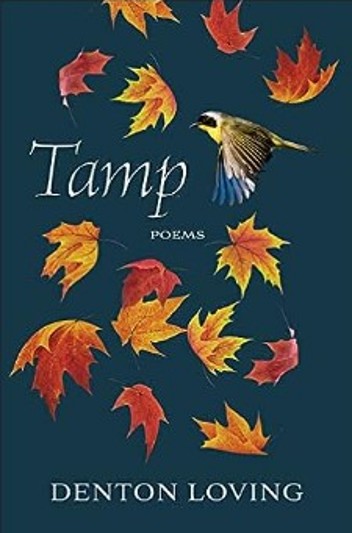

Loving, Denton.

Tamp: Poems. Mercer

University Press 2023. 64 pp. $20.00.

In his opening essay, “The Lyric: A Personal

History” in Said-Songs:

Essays on Poetry and Place (Mercer University Press, 2021),

Jesse Graves states the following:

In his opening essay, “The Lyric: A Personal

History” in Said-Songs:

Essays on Poetry and Place (Mercer University Press, 2021),

Jesse Graves states the following:

“The

elegist confronts a seemingly impossible, certainly inevitable task:

the event of loss must be articulated and made comprehensible to the

audience, regardless of its magnitude or its proximity. Every

sufferer of loss must absorb or deny the event, must attempt—or

not—to work through it, and the elegist must carry this organic

process through an artificial gateway into the realm of the poem

itself, the poem in response to the loss.”

The operative word in Graves’ opening line is

confronts; the root of

which, confront, comes

from the French word

confronter, which means to border or to bound. It’s fitting, in

this sense of language, that grief and confrontation elicits a

connection to borders, because grief often seems to lock an

individual into themselves. As Graves writes “the event of loss must

be articulated and made comprehensible to the audience.” In his new

collection, Tamp, Denton

Loving regularly confronts grief, with results of tender, meaningful

poems that explore the ideas his poem “The Broken Man” closes

with—“the miracle and magic of / the dead breathed back to life.”

Tamp opens with “Hurtling,” a tender poem written in couplets, which help to further set the scenes of the book. The speaker, “five again,” is filled with anxiety, but the father’s comfort helps to “quiet the starlings in [my] belly.” This leads the heart of the poem to truly shine: “I know I am safe as long as he’s close.” Right from the first poem, it is clear that Loving’s collection concerns itself with safety and softness, despite the rough, unpredictable nature that hurtling would imply. It is through this softness that Loving’s poems shed light toward the direction of healing. Loving’s poems also explore the duality of physical and human nature, with many poems concerning farming and, to give a nod to Wendell Berry, “the care of the earth.” Poems like “There is a barn” and “Remembered by Name” are particularly reminiscent of Berry’s essays from The Gift of Good Land (North Point Press, 1981). The book’s theme central to unity and homage to the land aligns greatly with Loving’s landscape and farming poems.

I was also struck by the variety of influences in the collection:

Kevin Young, Judith Light, among others. Kevin Young’s influence

comes from a playful, tongue-in-cheek poem titled “Cows Don’t

Consider Oblivion” that alludes to Young’s poem “Oblivion.” Further,

Judith Light, well-known actress, especially known for being Angela

Bower in the ABC sitcom Who’s The Boss appears in a dream poem

simply titled “Upon Meeting Judith Light in a Dream.” That poem,

fused with pop culture, lines up with Loving’s vision of grief and,

once again, showcases a softness that proves enlightening.

These influences, much like the grief and the landscape it leaves in

its wake, help shape and cultivate poems that prove enduring and

encourage re-visitation. The poem modeled after the infamous

Augustus Saint-Gaudens statue is, in particular, one of the most

fascinating pieces of the book—its title is taken from the work

itself: “The Mystery of the Hereafter.”

“The Mystery of the Hereafter” is a poem that has haunted me since

my first reading. The poem is inspired by the Adams Memorial—a grave

marker in honor of Marian Hooper Adams and Henry Adams. It is housed

in the Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, DC. Henry Adams’s ghost

stirs in the poem from the first line:

Do not call it grief.

“Grief” is what many reporters gave the name of the shrouded statue,

much to the irking of Adams. The poem is written in couplets that

suggest unity and togetherness, lending to the poem’s wielded power

until its close.

Another poem I keep going back to is “After My Father Died, I

Marveled” that opens:

“In the field / cattle grazed, unbothered by the coming / winter,

unfazed by the farmer’s absence.” The poem, formatted markedly

differently than those previous, focuses on quick, exacting images

of what is seen and

who is unseen. The poem,

much like the speaker, continues forward by filling absence with

sustenance: “I ached with hunger— / the drive-through ladies kept

taking / my orders, kept taking my money.” This ache is also

magnified by the drive “back and forth / from my house to my

father’s house even though / he wasn’t there.” There’s a great

strength to saying something in such direct language because through

that directness comes the gateway that Jesse Graves refers to. That

gateway leads to tenderness for those who came before, life for the

living, and grace for those who will come after. The poem ends with

a sense of lucidity that can only come from grief: “…but / I was too

spent / to cry or be angry / or feel anything except / the motion of

it all.”

Denton Loving’s Tamp

challenges the notion of elegy–the traditional view typically lensed

in three stages: lament, praise, and solace. Contemporary

collections surrounded by grief adhere often to a creative decision

to “make it bright,” but Loving reminds us that grief is tenacious

in its nature. It comes in poems like “Learning to Drive” and

“Riding Lawn Mower”—poems that fuse memory and life lessons-learned

philosophy that comes directly: living one’s life. These poems

embody the power of memory possessed by the living when honoring

those that have gone before us.

This line of thinking is especially indicative in “We Are Called to

Reinvent Ourselves”:

…I attempt

to retrace my path home, but the trail moves

or I do

and in a flash, I forget all I should know.

Further still, the poem continues:

You can spend a lifetime memorizing a place,

the trails and trees, the land’s lay and water’s flow

dividing your dreams from those

who walked there before you.

This poem is reflective of a great power in

Denton Loving’s poems: poems without flourishes, and the language is

direct and authoritative. That authority comes from Loving’s ability

throughout Tamp to fuse

memory and influence to honor both his land and his lineage.

Denton Loving's Interview

Denton Loving's

Poems and Bio

| Archive | Submissions | About | News |