~ Delta Poetry Review ~

Allison Joseph Interview by Stephen Furlong

SF: First and foremost, thank you for taking the time for this interview. In light of all of your responsibilities (teacher, director, editor, poet), how do you manage your time? What helps you unwind?

AJ:

I manage my time pretty poorly—in terms of things like day planners,

online scheduling, etc—I’m terrible at that! But I do use time pretty

wisely when I’m forced into situations that demand it. I write when I’m

on a train or plane. I write in hotel rooms. I write in my head when I’m

out for a walk.

Over the years, I’ve had a lot of “hobbies” to unwind: calligraphy,

jewelry making, harmonica, guitar, drawing, knitting, crochet—I’ve

failed at every single one! The only one that’s stuck is running (and

I’m not as fast as I used to be).

SF: How does your role as a teacher help your writing? How does your writing help your teaching?

AJ: Yes, because teaching forces me to think about all the issues I should be thinking about as a poet and artist. In order to teach any concept, you have to internalize it and then learn how to relay it to other people who may or may not have the same passion for it as you do. That’s bound to help my own work when I return to it. I create exercises for my classes, and then do those exercises myself, so I can see if they actually work.

SF: One of my favorite things about you is your use of the chapbook—it seems like you’ve got a new one each year!—what draws you to the chapbook as a medium of getting your (and now others with No Chair Press!) poems out in the world?

AJ: Chapbooks are perfect in so many ways. They can begin a career, sustain a poet in mid-career, or be a coda to a long poetic career. They are cheaper to produce than full-length books. They allow for experimentation. They can be produced by hand. They’re fun. Sometimes you don’t want the whole pizza, but a slice or two is nice. Chapbooks are those tasty slices.

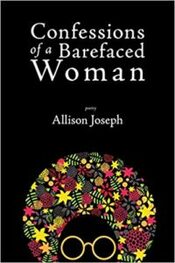

SF: Your most recent book Confessions of a Barefaced Woman (Red Hen Press, 2018) has been well-received considering it was a finalist for the NAACP Image Award in the Poetry section, had a poem (“Flirtation”) reprinted in the Sunday New York Times, among many other nominations and finalist contentions. It also was winner in the poetry category for the 2019 Feathered Quill Book Awards! All of this to say, I’m curious, as a poet and human, how do you navigate these successes and continue to do the work you do?

AJ: The success of that book was quite surprising. I attribute it to several factors. Red Hen Press has been very supportive. I decided to enter it in every contest that interested me—which is an expensive process. I had just gotten a promotion to full professor (which was about 15 years overdue, but I wanted it to be a slam dunk). So it’s garnered more kudos than any other book I’ve published. But that’s more a matter of me having the time and the energy to let it compete.

SF: I find that your poetry explores form quite often (My Father’s Kites, Steel Toe Books 2010 and The Purpose of Hands, Glass Lyre Press 2016 immediately come to mind), and I know you’ve spoken to the point that form gave you control, specifically in response to grief, but, is there a moment when you’re writing that you notice form becoming a part of the poem, or do you try to get the ideas out first, then worry about form after?

AJ: Not really. I generally know from the first line if a poem’s going to be in free verse or will be in a set form. There are times when I think in sonnet, or ghazal, or villanelle. Other times, I know I want to tell a story, so it’s much more likely that I’ll use free verse. When a line comes to me demanding to be a refrain, it’s likely I’ll use it for a French form.

SF: I’m re-reading Langston Hughes’ autobiography The Big Sea (A.A Knopf, 1940) and he writes: “For my best poems were written when I felt the worst. When I was happy, I didn’t write anything.” From your experience, when do you turn to poems?

AJ: I write whether I’m happy, sad, angry, etc. My moods are irrelevant. If I’m interested in following the music of a particular line, it doesn’t matter whether I’m weepy or joyful. So I’m always turning to poems—whether writing them, reading them, choosing them for publication, etc.

SF: I don’t like ending interviews on the question what are you working on because it feels invasive, so if you wouldn’t mind, can you talk about something that has recently (say, within the last six months) truly fascinated you and you feel like the world should know about? (If you are not interested in this sort of thing, I can remove this question).

AJ:

My next full-length book, Lexicon, is about to go into

production at Red Hen for a 2021 release. When the press asked me to

describe Lexicon, I wrote this:

Lexicon is a worthy successor to Allison Joseph’s award-winning

breakthrough, Confessions of a Barefaced Woman. This time

around, this self-professed “barefaced woman” is setting her

sighs/sights on language and what it does for and with and to her.

Joseph loves language, making it her slippery passion in poems about

childhood griefs and fashion faux pas, movie musicals and empty

airports, “rules” for writing and rules for reading. Though Joseph loves

language, it doesn’t always love her back—but in her wise, readable and

imaginative way, she persists while documenting the minefields of racism

and sexism. Joseph finds joy in the most unlikely of places, and in

Lexicon, her adoration for the written word lets us see those

places in sharp and evocative relief. All hail this bounty, this

Lexicon!

One skill I urge all writers to get is the ability to write a blurb

about one’s own book.

Confessions

of a Barefaced Woman, by Allison Joseph

Confessions

of a Barefaced Woman, by Allison Joseph

Reviewed by Steven Ostrowski

I’m tempted to confess that I am personally more strongly drawn to what might be called “experimental” poetry (as long as it is coherent) than I am to poetry that might be described as “accessible” or “plainspoken.” I often find poems deemed “accessible” to be overly familiar either in form, content, or language. Of course, the can of worms one opens with the very mention of the word “accessible” in the context of contemporary poetry is a huge and brimming one and, fear not, not the subject of this review —except to say that I find the poems in Allison Joseph’s Confessions of a Barefaced Woman both highly accessible and extraordinarily compelling. Predominately semi-autobiographical and first-person narrated, and presented in a roughly chronological order, these are damn good poems. They’re crafted carefully, artfully, sometimes formally, and always unpretentiously. The lines are tight, yet, like tiny novels, they reveal complex characters placed in powerfully vivid and memorable scenes, scenes marked by a fearless and intimate honesty. And although the stories these poems tell are mostly about being black and female, and feel deeply personal, the attentive reader of any poetic persuasion and of any race or gender will find his or her mind and emotions enriched and rewarded, poem by provocative poem.

Joseph’s poetic journey in Confessions takes the reader from a

complicated New York City girlhood to an adulthood of writing, marriage,

and wide-ranging reflection. While some of the poems are humorous and

playful, many are devastating. Themes Joseph explores include the

complications inherent in family relations, contemporary culture and its

effects on individual identity, and racial identity. “On the Subway,” is

a poem about both contemporary culture and racial identity. It is also

about innocence lost. In the poem, the young black female narrator,

riding the subway home from school, encounters a man with eyes that are

“bloodshot and raw” and whose brown skin is “deadly gray.” He slouches

across from her in what has become an otherwise empty car. The man the

girl discovers when she lowers her chemistry book is exposing himself.

Frightened, the girl’s hope is that “because he’s black and I’m black…he

won’t hurt me,” a line I found stunning for its painfully touching

naiveté and for its bald expression of desperate hope. The girl manages

to dart out of the car physically unhurt, although one senses she’s been

scarred by the encounter.

In “Father’s Mother,” the angry narrator confronts her cold, judgmental

grandmother. The poem is a direct address to the grandmother, and it's

opening lines cut to the core.

How miserable you were,

unable or unwilling to do

comforting things expected

of grandmothers…

The anger, the poem will go on to reveal, stems

largely from the grandmother’s treatment of the narrator’s father and

the effects that treatment had on him and subsequently on the narrator

herself. The grandmother, light-skinned, is biased against people with

darker skin; she complains a lot; she has no friends; she is suspicious

and unsmiling. Most damning of all is the fact that the grandmother

could show no love or physical affection for her son or for her son’s

daughter.

Did you

not touch my father

because his father left you

and a few lines later

Did you not touch my father

because his father had other women

other sons?

And late in the poem, this stark line:

I was too dark for you to love

*

Another poem that explores race and racial identity is “To be Young,

Not-So-Gifted, and Black.” By now, the narrator is a grown woman, a

professor teaching a college poetry course. One of her students has

written an evaluation of the course

I wouldn’t have taken this class

had I known all we were going to read

was black poetry!

But that is not in fact the case. The syllabus

only includes two black poets and the narrator wonders

Was it my black face that student hated,

my lips turning every poem into black poetry,

into what so offended him or her that poetry

was now forever spoiled?

That second line, it strikes me, encapsulates

perfectly a certain kind of bigotry, that of a racism so unconscious and

pernicious that it grants hatred a magical power: for those under its

spell, anything can be contaminated by race.

So how does the narrator

respond? Invoking the spirit of Lorraine Hansberry, she asks herself, “What

would Lorraine do?”

I bet she’d have something

Coolly trenchant to say, and she’d say it

So wittily that the student would want to be black

The poem ends with lines that are, for me, among

the most powerful in the entire book.

Lorrain’s words make this burden of black

something I can handle as I add more

black names to the syllabus, more chances

for the people who will always hate my skin

to hate it even more, learn less.

Learn less indeed! My only criticism of this poem

is that it might be more appropriately titled “To Be Young,

Not-Very-Bright, and White.” But I suspect Allison Joseph is too

generous a soul to give her poem a title like that.

*

Confessions of a Barefaced Woman is by no means void of humor, of

keen observation and wry commentary on everyday aspects of life. The

poems that take on the hard subjects are leavened throughout by poems

that view ordinary life through Joseph’s confident, clear-eyed, often

amused lens. A couple of examples: in “Poem for the Purchase of a First

Bra,” the narrator expresses gratitude to a saleswoman who sensitively

helped her choose and purchase her first bra; in “Elegy for Rick James,”

the narrator remembers the sexy music of James “stroking me in places/I

didn’t know I had.” There is much, much more.

I confess that after reading Confessions of Barefaced Woman, I feel

chastened: there is such a strong payoff in these “accessible” poems

that I want more of them. And I want learn from the very talented, very

wise Allison Joseph.

| Archive | Submissions | About |