~ Delta Poetry Review ~

- Interview and Book Review -

Sheryl St. Germain's Interview by Dixon Hearne

Thank you, Sheryl, for agreeing to this interview with Delta Poetry Review. I know it is impossible to touch upon every salient point in an interview, but I know our readers will be very interested in your keen insights, observations, and experiences as a poet and writer.

DPR: Eudora Welty once

said that one place understood helps us to understand all places

better. You are a native Louisianan. How do you think cultural

influences from the south play a role in your writing? How does that

differ from regional influences in other parts of the country? What

is particular or unique about the southern experience as it relates

to writing—whether narrative or poetic work?

SSG: For some of us, place is perhaps the primary

shaper of voice. As a writer from the New Orleans area, I come from

a place surrounded with water: Lake Pontchartrain was three blocks

from our childhood home in Kenner, and the Mississippi just a couple

miles the other direction. Ditches that ran alongside our homes

provided incredible possibilities for discoveries as a

child—crawfish and snakes for us—and hurricanes and subsequent

evacuations also gave shape to my voice and personality. Early poems

of mine, such as “The Lake” and “Going Home” offer great examples of

how both culture and nature were in my blood from the beginning. I

love drama and color; the focus on sensory perceptions in both my

writing and in the fiber art that I also work with surely comes from

growing up in New Orleans. Food and drink play a large part in my

early poems, an aspect of place that sometimes gets overlooked. I’ve

written poems and essays inspired by gumbo, red beans and rice, and

bread pudding, for example. Much of my work has also been influenced

by the ebb and flow of water and flood, both as a theme and formal

inspiration.

It’s tempting to flatten

out cultural experience, to say most people from any given place

will respond to it similarly, but that couldn’t be farther from the

truth. In my case, I have a love-hate relationship with the South

because of the many tragedies that befell my family there, mostly

related to substance abuse. I moved away from New Orleans when I was

almost 30 for graduate school but never returned to live because

there was a part of me that feared falling into the swamp of

addiction and alcoholism that took so many in my family. There was a

kind of excess in my family that centered on eating, drinking, and

sometimes violence that frightened me, much as I loved so much about

the city, Mardi Gras and gumbo, swamps and bayous, the music and

diversity. I’ve written about this ambivalence in several of my

essays, and I think it also comes out in some of my poems.

New Orleans has a

specific character—one might say it is a place of strong

personality—unlike that of, say, Lafayette, where I also lived for a

time, or Slidell, which I have only driven through. I think the

regional differences that make my voice what it is are what’s most

important. That might not be the case with someone who grew up in

Iowa, for example, where I also spent many years.

DPR: What is your most recent book

publication? Tell us about this collection. It’s such an evocative

title. Where did it come from? Does each of your published books

influence the content or poetic style of subsequent poetry

collections?

SSG: My most recent publication, out this year, is

a hybrid collection of lyric essays and poems called Fifty Miles

(Etruscan Press). It followed a collection of poems, The Small

Door of Your Death (Autumn House Press) that was published in

2018. I see the two as companions in that they both explore the

death of my son Gray in 2014 of a heroin overdose. Most of the poems

in The Small Door were written either before or very soon

after my son’s death. At that time, I was struggling to find a

narrative that would help me articulate and maybe even understand

his death, so these poems are pure lyric, short and sharp as a shard

of glass. They investigate a mother’s grief and present, I hope, a

compassionate but unsentimental portrayal of a son, his mother, and

their tragic journey. The title of the collection refers, literally

to the needle mark the detectives found in my son’s wrist when they

discovered him, that mark a small hole, the opening that allowed the

heroin into his veins, which led to his death. But I also hoped the

title would be understood metaphorically. The way to the kind of

death my son experienced was through a narrowing of his life and his

curiosity about the world. As he became more and more tied to

drugs—and there were many, not just heroin—his world shrunk until

there was finally just one door left that led, ultimately, to his

death.

Fifty Miles

contains some poems that I didn’t think would fit in A Small Door,

and they are sprinkled between longer essays that explore cultural

issues that might have contributed to my son’s ultimate choices,

including his being diagnosed with ADHD at 5 and being prescribed

Ritalin and Adderall, which were the first drugs he ultimately

abused. There’s also a very long essay about playing video games

with him; I wanted to tell a story that didn’t demonize video games

but showed how that playing connected us. These are just two

examples of pieces whose narrative imperatives would not have worked

well in poems.

I have been alternating

publishing poetry and poems in the last twenty years. It seems

almost as if once the poetry book comes out, I realize there is so

much more I could have said, and the essayistic impulse takes over.

And once that book is out, I long for the pure lyricism of the poem

again. I feel blessed to be able to work in both genres.

DPR: How important do you think it is to

experiment with form, or to at least have background knowledge of

the way certain forms of poetry work?

SSG: I think it’s very important for poets to

understand form before they begin to experiment with it. In my last

years of teaching, I began to teach the prose poem before teaching

sonnets or villanelles or even traditionally lined poetry because I

wanted to make sure students understood the power of the sentence

before they began to break it up into lines. I found that strategy

worked well, and after having worked with the prose poem, they were

then able to write lined poems whose line breaks were more

intentional, and about which they could talk. After that, we began

to work with some traditional forms. If you don’t know how to write

a sonnet, you won’t understand how to write a broken sonnet or know

how to play, or riff off that form.

DPR: We all deal with love and loss at

various points in our lives. You write eloquently about the loss of

your young son. It is often asserted that writing is therapeutic.

How has writing helped you confront and deal with your personal

loss? Do you recommend it as an intervention, i.e., more than just

simple exercises?

SSG: Writing has often helped me work through tragedy. I have kept

journals all my life, and the ability to shape something into a

paragraph or a poem allowed me to have the (more often than not

false) sense that I had some control over a situation. The poem or

paragraph captured the experience, contained chaos if you will.

Writing can be therapeutic, and it can contribute to healing, but it

cannot substitute for therapy. I have had a therapist for over

twenty years, and that relationship has counted more in terms of

substantive healing than my writing has. Writing—especially poetry

writing—helps me to lay things out in all their complexity. Here is

the thing in all its horror and ambiguity, and maybe there is a

small insight that comes out of that. It helps me to imagine other

sides of a story, imagine what might have been, honor grief and

darkness. I think tragedy drives many artists, not just poets, to

work. While they are working, they are alive.

It must be said that the

reading of other’s works can sometimes be as healing as one’s own

writing. I have taught creative writing for many years in jails and

rehabilitation facilities where we begin by reading the works of

others. To read a poem or story that articulates a courageous vision

about some tragedy can be incredibly inspiring for the reader.

Especially powerful are those works that present tragedy without

moralizing or compromising a vision.

DPR: Your latest book, Fifty Miles

Etruscan Press, 2020), is a mix of poetry and essays. Might you

share a bit about the book, particularly its purpose and message?

SSG: The book traces my own journey and healing

from substance abuse as well as my son’s journey to death. The

title, Fifty Miles, represents two literal and metaphorical

journeys my son and I took separately. When I was in my twenties,

living in Hammond, Louisiana and attending Southeastern Louisiana

University, I spent some months shooting up cocaine with a lover. At

some point, I came to my senses (it’s actually much more complicated

than that, but read the book to find out!) and drove fifty miles to

Baton Rouge to stay with a friend who helped me recover. I took a

bus to Hammond two days a week for classes until I graduated. Over

thirty years later, my son would wake up one deeply foggy morning in

Dallas, Texas, where he lived and had been in recovery, to drive to

a small town fifty miles away, where he bought some heroin from a

friend and overdosed. Many of the essays in the book, including the

titular one, are lyric meditations on these two journeys.

Overall, though, I would

say this is a book about hope. Many of the pieces are about the ways

I stayed sane, or tried to, while Gray was creating and living in

ever troubling worlds, and how I worked with grief after he died,

specifically through traditional arts such as crochet, and through

traveling, gaming, teaching, and writing.

DPR: What guiding principles inform and

guide your poetry and essay writing? What themes and topics

(psychological, philosophical, emotional) appear most often in your

writing? What literary devices and/or approaches do you favor, if

any?

SSG: I am a great fan of metaphor and reflection in

both poetry and the essay. I love prose poetry as well as the lyric

essay, which I think of as being like a poem in old clothes. Prose

lyricism might be something I’d say that I love to work with. I also

love the work of poet Pablo Neruda and have always been inspired by

his Odas Elementales, a collection of odes to humble things

like socks, lemons, tomatoes, etc. I aim for the elemental in my own

work. I aim to work as a translator might—to allow something to move

through me to the page. I don’t want the reader distracted by

thinking about the writing but rather to come out of a poem or essay

moved and thinking in new ways.

I also love what Franz

Kafka is said to have written about good literature, that we should

read only the kinds of books “that wound or stab us.” A book, he

wrote, “must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” I hope that

my work feels like that axe.

Book Review by Darrell Bourque

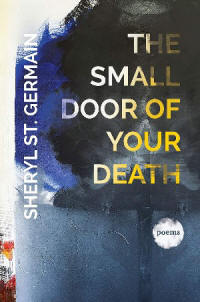

The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain, Autumn House Press, 2018;

cover art, Gray by Morgan Everhart, oil on canvas, 2015

Reviewed by Darrell Bourque (Poet Laureate of Louisiana 2007-2011)

Sheryl

St. Germain’s The Small Door of Your Death is a memory poem for

Gray St. Germain Gideon, her son. The composition is a

confoundingly disarming poem and a powerful triggering work. I hear in

it echoes of two of the most elegant recent poetic-philosophic works on

loss and grief, Brenda Hillman’s Death Tractates and Edward

Hirsch’s I hear the moaning of Niobe. I see in it the work

of the textile artist who makes grief quilts, personal grief quilts for

those close by and I see in it the work of world-wide/culture-wide grief

quilters like those whose quilts gave us the AIDs Quilt Project

addressing still undocumented loss not unlike the alcoholism epidemic

losses that have long plagued our country and families and the opioid

and drug epidemic that took her son Gray from her.

Sheryl

St. Germain’s The Small Door of Your Death is a memory poem for

Gray St. Germain Gideon, her son. The composition is a

confoundingly disarming poem and a powerful triggering work. I hear in

it echoes of two of the most elegant recent poetic-philosophic works on

loss and grief, Brenda Hillman’s Death Tractates and Edward

Hirsch’s I hear the moaning of Niobe. I see in it the work

of the textile artist who makes grief quilts, personal grief quilts for

those close by and I see in it the work of world-wide/culture-wide grief

quilters like those whose quilts gave us the AIDs Quilt Project

addressing still undocumented loss not unlike the alcoholism epidemic

losses that have long plagued our country and families and the opioid

and drug epidemic that took her son Gray from her.

I see in The Small Door of Your Death a

flip in the disquisitions of Hamlet, this time a mother enthralled and

entrapped in the tragic loss of a son. I hear in it what Dmitri

Shostakovich scores in his 7th Symphony, what Anna Akhmatova must have

felt during those dire days in Leningrad aching for the loss of her

imprisoned son, her city, and her country. What St. Germain has come to

in response to her grief is the creation of a symphonic tone poem,

informed as much by music as by her gifts as a teacher, a Words Without

Walls social worker, and a poet.

This book reads as much as one long poem as it

does as a collection of titled shorter poems. And, it has all the

hallmarks of the kinds of longer musical works St. Germain is so

familiar with and which she has long allowed to influence her work in

poetry.

The first poem in the collection, “Loving an

Addict,” announces the traditional A and B themes of quartets,

concertos, suites, symphonies:

“it was always fights or lies

maybe at the end

I preferred the lies

Much of Part 1 is exposition: the past, the

heritage, the setup, and the ties to addiction that mother and son have

as part of the families they grew up in, as part who they are. Part 1

also introduces one of the major variations on a theme in the work, the

motif of divination and the Suit of Swords from the Tarot cards. The

Swords in the Tarot are consciousness guides, intellect guides, seeing

and understanding guides.

The Swords motif is used 5 times in part 1, and 5

times in part 2 which begins and ends with the poem “Rehab”:

we’re here, our skin thin as parchment

…

It’s hard to hope, but we cling

to any worm of it

the lights

in the rooms here, after all, are so bright

The motif will not appear again until Part 5 and

only once. In this latter play on the motive, the poem invokes Einstein:

“ We should take care not to make the intellect our god,” and shifts to

a woman lying on the stone floor of a church trying to conjure a god she

can believe in. What we are left with at the end is the unending

restlessness of the journey into understanding, knowledge, clarity,

transparency:

… all she feels is the edge

of her spine, resting for now,

as much as swords can rest

The resting or lack of it, will be absorbed into

the fabric of the larger composition, absorbed as much as it can be

absorbed but still felt to the very last poem in the collection.

Part 2 of The Small Door of Your Death

contains the poem “[it comes down to this],” a prefiguring of the

musical suite that will become Part 3 of the book. In this poem (also a

four part mini-suite very near the center of this memory poem) we get

the title of the collection and a shift in the way memory will work as

the themes are further developed:

you chose the vein

in the back of a hand

to carry

this last intimacy

a puncture mark

the small door

of your death

“Benediction, a Suite” a prose poem section of

the work comprises the whole of Part 3 and it is a sort of musical hinge

holding the diptych created by Parts 1 & 2 and Parts 3 & 4.

“Benediction, a Suite” is skein, cord, knit, crochet, weave, all on

Gray’s name: “A name for one we hoped would follow his own path, wild as

wolf or heron or whale, though we knew, too, that gray’s the color of

mourning, ambiguity. … I grieve by stitching a blanket of the most

sumptuous yarns, each a slightly different shade of gray …. … With each

round my hands remember your sadness and wildness, with each row a wish

I could have stitched your wounds…. … too late, these words of slate and

silver … grays dark as storm clouds … bone light as your ashes.

Part 4 is largely the music of confrontation and

lamentation. It begins with the “Viewing the Body” and with the

revelation of “Never again this body, never this vessel through which I

knew you.” It is the beginning of both loosening and realizations,

rituals of loss and departure: “The Drop” where the father murmurs

something like this being the “last Gray switch” in a meeting

where the son’s ashes are halved between divorced parents. The section

is further developed with poems on meeting the drug pusher, the

disposition of ashes, returning memories, and a tribute to Gray’s work

as a musician and to all the things good and otherwise that brought him

to his last work in the world.

The closing poem of Part 4, “Less a Song Than a

Compilation of Beats,” uses the title of one of Gray’s own musical

compositions, and the section ends without judgment, with a nod to the

very art that sustained him for as long as it could, and with the

suggestion that every song, and every poem, is a compilation of beats

and that few of them, if any, are ever finished. The poem itself I read

it is an anguished reconciliation leading to, not the final stages of

grief, but to another stage where the breathing is slightly different

and the count is somewhat, and only somewhat, more bearable:

we sewed you together during the day

you unraveled by dusk

frenzied and free,

each night you worked that song

you’d never finish

Movement 5, or Part 5, is a movement through the

grief. The poems become more and more the music of memory: Gray

remembered in Amsterdam, among the windmills, in France; Gray embedded

in reasons to live in red cowboy boots, in his mother’s favorite color,

in the first color she sang; and Gray woven into in the yearning tulips

at Keukenhof. If grief cannot be transformed, it drifts -- in poem, in

music, in nature:

Here in these fields, grief drifts,

alongside waves of tulips,

radiant, yearning.

The book ends with a coda of sorts, “Prayer for a

Son,” a poem filled with lyric beauty, with death absorbed into life

into death into life, filled with the prayerful silence that memory

sometimes brings us to. The ending is personal, intimate, sacred. Here

there are finally the last vestiges of song and the final compilation of

beats:

… may we be blessed to hear you

In song of bird and cricket

And then the final notes:

… and in the silence after

the poem’s last word.

The Small Door of Your Death

is so much

more than we come to expect from a book of poems. It is tractate,

disquisition, song, symphony. It is consolation and philosophy. It is

grief materialized right before our eyes, personal grief and grief that

grips communities and nations. It is ache. Loss. History. Dream. It is

also Hope and Solace, and how memory stands with us at our most

destitute times, how love finally, and love only, saves us.

| Archive | Submissions | About |