~ Delta Poetry Review ~

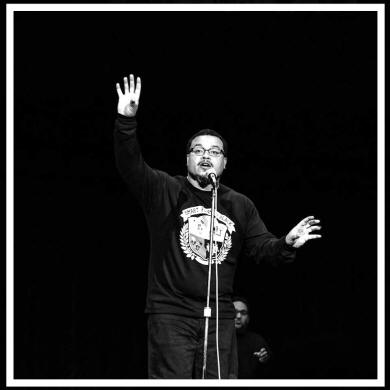

Junious Ward, Featured Poet

Junious “Jay” Ward

is a poet and teaching artist. He is a National Slam champion

(2018), an Individual World Poetry Slam champion (2019), author of

Sing Me A Lesser Wound

(Bull City Press, 2020) and

Composition

(Button Poetry, 2023). Jay currently serves as Charlotte, NC's,

inaugural Poet Laureate and is a 2023 Academy of American Poets

Laureate Fellow. Ward has attended Breadloaf Writers Conference,

Callaloo, The Watering Hole, and Tin House Winter Workshop. His work

can be found in Columbia Journal,

Four Way Review,

DIAGRAM,

Diode Poetry Journal,

and elsewhere.

Kodak 4200 Slide Projector Asks if I Ever Held

Hands with My Father

|

I. In the first picture my father’s hands

ain’t holding nothing but a cooking spoon

the wired remote, clicking to the next slide * In this one his hands are near a hollow steel pot first day as a cook at Hudson River State Hospital

he and Mom met there is a photo focused on her belly my hand walled within * Here a custodian covered in grease & callus—hot water heater memento He needed to be loved/fixed

instead I’d pretend not to see him in school head down timid waving as he passed

II.

light dust an odd hum blink of machines oscillating past lives against a transfigured wall |

I hold a lifetime flashing against yellowed plaster empty where I imagine his hand reaching impossibly toward his hands really could fix/love whatever if I’d let him Memory merges with the present— hospital room tethered like his thin

fingers resting in mine |

The Narrative

The stories tell so similar I can’t tell if I’m

dreaming or

remembering hands pinned to the ground, hands

penned

writing some manacled vision of the future.

Hands behind the wheel or up, a toy gun, a

licensed gun

—daughter watching, mother watching, father,

son, cousin.

The stories be so similar I can’t tell if I’m

dreaming or

reaching for my ID, stepping out of the car,

compliant, viral.

The assassination will be Live, my brother, viva

la revolución,

igniting some Orwellian vision of the future.

No text by 10 p.m. No call by midnight. My

biggest fear—

babygirl gets pulled over and I find out through

social media.

The stories are so interchangeable I can’t tell

if I’m dreaming or

the body camera was turned off. I know you’re

tired of this poem,

its nagging anticipation, its blame-song, its

gnawing complaint,

all poems, inviting some pissed-off vision of

the future like—

open up, hands where we can see ’em, he’s got a

gun! he’s got a gun!

But I assure you, I am shopworn writing this

poem, more than you are

of hearing. These stories—so kindred, I can’t

tell if I’m dreaming or

fighting everything, everything in me, to

envision a future.

From

Composition

(Button Poetry, 2023); reprinted with permission by the author.

I Love the Hometown I Had to Leave

Rich Square is a small town with a pull

strong as nostalgia. Small

like an atom you need to stay and escape

from, split without exploding.

I grew up in the chemtrails of segregation.

My white mom went to the Black church,

not far from the white church.

My white friends took a different bus,

played at the same school but never

the same house, grew up under the same flag.

I played in the woods, or on Creecy Lane

with the two Maurices, pig farm across

the street, cotton field down the road,

corn next door, humid, hot, and hazy.

Gravel driveways announcing visitors

like a crunchy doorbell. One stop light.

Pickup trucks and white friends—

both with Confederate flags.

Water hoses doubling as water parks.

Cadillacs and tractors. Dirt roads and street

lights.

Juxtaposition is common, like South moving

North,

like New York cousins boomeranging back

to this ground. Home is a return to dust, root.

Of course I remember Black kids being told

the pool in Jackson was closed while dozens

of kids could be seen splashing over a shoulder.

Of course I remember being followed

in the store for a zebra cake, called “boy,”

him tapping his waist. But what brings me home

is what’s inevitably mine; riding around

Chapel Hill Road like I own this, the bridge,

the graveyard my father is buried in, home

of the Rams like I own this, return of the

bubble

goose, cornbread and corner-store swag, like I

own

this, Mad Dog like I own this, Southern Comfort,

Boone’s Farm, Strawberry Hill after the football

game,

Spirit Week bonfire with kids who make temporary

friends with buying-age bums—symbiosis of sorts,

Styrofoam cups, 8 Ball—an Olde English accent

sloshing to asphalt for the homies like I own

this,

recurring orbit like they know my name still.

From Composition (Button Poetry, 2023); reprinted with permission by the author.

The Flat Harmony That Shivers the Air

after Kwame Dawes

I think, maybe, I’ve always known grief

tangentially. I am mourning, at the heart

of it, someone else’s tragedy. A sudden loss

to me is moreso a spouse’s loss, or mother’s,

or maybe even the nurse who had to watch

another iteration before her shift change,

reassure, reach momentarily across

a stranger’s shoulder while prepping the room

for the next emergency. I think I’m seeking

a branch. I want it to stretch to my numbed

limbs. Take this cup. Even prayer is a thief.

No one has touched the box of pizza.

The air is a blender. We spill over each

other like bubbling water. Mucus on sneakers.

Our bodies barren and waterless.

“Our” helps me acknowledge others in the room

while distancing myself from feral screams

gutting the halls. “I think” helps me avoid everything

definitive. My saving grace. I can say “we

are losing something” instead of “I am empty.”

Because who am I, at the heart

of it, to risk consoling myself

when tomorrow the closets have to be emptied

and the house might go up for sale?

Arrested at Gethsemane

At the foot of the Mount of Olives,

the boy is a garden, he is tempted

to become someone else.

There is a trial coming. He knows

the outcome. The boy is a pocket

of holes foraging lint to survive.

The boy is his father’s son

and mother’s miracle. The boy

is being raised toward the sky,

a reckoning. There is a trial

coming. He knows the outcome.

The boy is a cigarillo. He is lifted,

he is lifting. The boy is a thorn.

The boy is a droplet or a deluge

or insignificant. The boy is waiting.

He knows the outcome.

There is a trial coming.

The boy is my only chance

to get it right. He is wasting

in real-time; on a tree,

on the street, on television.

The boy is a version of me behind

a

heavy door. Who will roll this

stone

away?

The boy tells me “stand, again,”

and, even knowing the outcome,

I do. I am first on my knees reliving

every past, being choked, gasping.

Then I stand and pray

for those who pierced me,

so in this life I might be

a savior.

| Archive | Submissions | About | News |