~ Delta Poetry Review ~

Sara Henning's Book Review by Stephen Furlong

|

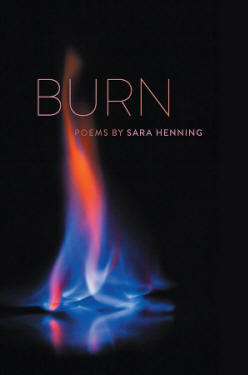

Henning, Sara. Burn: Poems.

Southern Illinois University Press, 2024.

74 pp. $18.95

In the essay “In

Search of a Language” from her 1995 book Object Lessons: The

Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time, Eavan Boland

posits that “[T]here is a defining moment which comes early

in a poet’s life. A moment full of danger. It happens at the

very edge of becoming a poet, when behind there is nothing

but the mute terrain where, until then, a life has been

lived and felt without finding its formalization.” In

spending time with Burn by Sara Henning, readers will

recognize the defining moments in the speaker’s life as

those surrounded by flame, giving way to the duality of

flame itself: destruction and rebirth, love and loss. But

what endures, what comes after, is a book of strength,

influence, and determination—Sara Henning’s Burn is a

field map that guides readers through the flames to find the

clearing, and time and time again, the clearing is defined

by love.

In the opening poem, “Galveston, Texas,” Henning begins with

an arresting image:

When Brown Pelicans torpedo

the Texas coast, flare their gular pouches

to sieve for prawns, they look

like bombs falling from the sky.

Tell me the world is on the verge

of ending, and I’ll believe you.

The raw nature of the birds renders the

speaker “sea-shocked” and, further still, “[E]ven the wind//

seems complicit, brutalizing dunes,” allows the reader to

recognize the full magnitude of power in this poem. An early

thread in Henning’s book is the impact of naming—this is

revealed through the “warlike names” of the pelicans: “pod,

squadron, fleet—”; as such, this thread stitches an

enduring focus and command to Henning’s poems.

Speaking of naming, there are many influences weaving

through Burn – book and section epigraphs ranging from Delmore Schwartz to Tennessee Williams to Toni Morrison

provide glimmers of insight into the poet and the poems. As

an epigraph lover myself, they are streaks of light through

the window blinds, but reach the window and open the blinds

and behold: a profound, meaningful experience awaits.

Speaking of light—one poem I keep returning to is “A Brief

History of Light.” Written across eleven tercets, Henning

opens with another striking image:

They will always be love letters,

closed caption letters unspooling across

the TV My mother, hard of hearing,

watched her stories in silence.

Guiding Light, One Life to Live,

living room lit by two Tiffany lamps.

Simply put, there’s great tenderness to Henning’s words

here, and the love in this poem is palpable. The Tiffany

lamps also certainly shine in the speaker’s memory, as

Henning writes further:

How many times did I stare into

a lampshade, its luster blunted through

coiled bronze and blown favrile

the canopy of glass in rich charade

all night?

Favrile glass, which was patented by Louis Comfort Tiffany

in the late 1890s, is revered for its hand-crafted nature

which, in turn, adds depth to this poem even further still

because of the precision and the focus wielded by Henning

herself. Speaking of hand-crafted nature, Henning works

magic as the poem’s landscape becomes the speaker’s youth:

…I’m tilling mica from soil at recess,

swearing it would catch fire in my hands.

I imagined angels tunneling through

layers of earth, catching their wings

on oak roots, bricks, and those little wounds

lodging there, waiting for me

to dig them up with sticks.

For as much as the poem is about light,

the poem can also serve as a field map for faith. The author

notes in the back of the book indicate this poem nods to

Billy Collins’s titular poem from Questions about Angels

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991); arguably, that poem

itself is a tongue-in-cheek meditation on how angels pass

their time, as well as the healing power of dance.

Conversely in Henning’s poem, by imagining angels coming

from the ground as opposed to the sky, the readers of this

poem can feel the speaker’s swelling pride in uncovering

“Goody’s barrettes” which makes the poem’s close—one that

brings those lamps that lit up the living room earlier in

the poem—into the speaker’s possession even more

rewarding. To me, this poem alludes to Eavan Boland’s

defining moment I spoke to earlier and, further still,

Boland writes “all the rough surfaces give way to the polish

and slip of language.” In Burn, the rough surfaces

of Henning’s poems are often rife with flames, embers, and

ashes.

However, to continue the metaphor, the

memories locked in this poem are like that of kindling, but

here’s where Henning’s strength to wield and operate

language allows for a sense of healing, of understanding,

that may not have been there in the initial formation of the

memory. That is because, through the unearthing of seemingly

miniscule trinkets like barrettes, a closer reading reveals

the healing happens through the uncovering and the

unearthing. That, just as well, could be the poet’s work: to

uncover and unearth. And, as such, this notion speaks

volumes to exploration Henning does in not just this poem

but the poems in Burn as a whole.

That’s where the healing happens.

Speaking of healing, the last poem I

want to touch on before I close this review is “Drive-In

Nights”; the poem is a kind of sestina-like variation,

especially with its word repetition and tercet envoy that

closes the poem. The poem opens with a Dorianne Laux line

which, just as well, could speak to the book’s intent:

you know love when you see it,

you can feel its lunar strength, its brutal pull.

As a lover of words, Laux’s use of

brutal strikes me just as a recurring word in Henning’s

poem strikes me, too: mercy. Given the context of the poem,

watching Die Hard with a loved one, the speaker in

this poem opened my heart with this question: “Who would

save us now?” And further still my heart opened with the

braiding of the poem’s narrative structure:

I can’t resist a man who’d kill

for his woman, a Johnny-come-lately who mercies

no one. I married you, husband, when you side

-swiped my heart. Terrorists fire,

take hostages. Hans Gruber calls shots. Once, we

caught fire

when we touched. In the fury of summer, got hitched.

We’ve fought, loved, made up in continuous cycles.

The fusion of movie plot with life story

is revelatory, and what’s striking to me is the poem’s

directness. As a teacher I once had would say, the poem

wastes no steps. This poem encompasses the love and passion,

the intensity and desire, which speaks to the collection as

a whole. Henning is also keenly aware of the poetic line

here, offering exciting dual meanings and thoughtful lines.

This poem makes me think of a Galway Kinnell line I had

taped to my writer’s desk for some time: “the secret title

of every good poem might be ‘Tenderness.’”

I would wager Kinnell’s adage rings true

for many of Henning’s poems housed in Burn.

Burn

is a book that interrogates how love takes shape in our

lives – and the book’s range is a testament to the effort

Sara Henning put into curating this text. I admire, with

great regularity, her exploration of form because these

moments are where Henning herself wields flame and creates

enduring poems like “Stealing Ariel” and “A Brief

History of Fire” that also anchor the book.

Simply put, Sara Henning’s Burn

is a rewarding and nourishing book. |

| Archive | Submissions | About | News |